Agnant shares anecdotes of Haiti, belonging

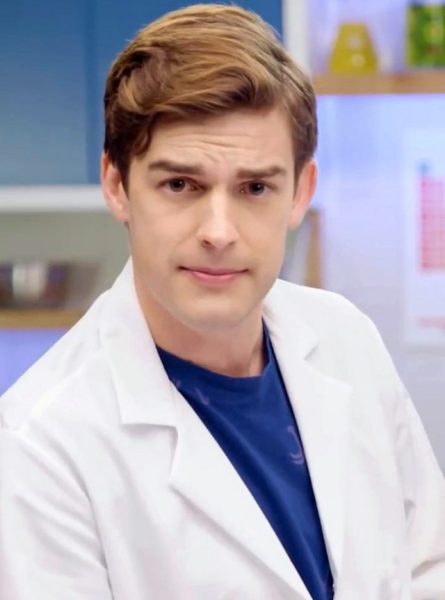

Marie-Célie Agnant relocated to Canada from Haiti in 1970. Pictured above in the 70s, Agnant became involved in Montreal’s feminist and environmental activism scene. Courtesy of Flickr

It was 1957 when François “Papa Doc” Duvalier became the president of Haiti. After rewriting the nation’s constitution and consolidating power, exiling and executing his political opponents, Duvalier established an authoritarian family dictatorship. During his rule, an estimated 30,000 Haitians were killed by their government. He was succeeded by his then-teenaged son, Jean-Claude, who neglected his constituents in favor of maintaining his lavish playboy lifestyle. The “Tonton Macoute,” a paramilitary force, regularly murdered and tortured Haitian people. Between a rash of diseases, a failing infrastructure and Jean-Claude’s reckless spending and cruelty, thousands were either killed or left Haiti during Duvalier leadership.

Author Marie-Célie Agnant was one of those people. She left Haiti at age 16, migrating to Montreal. On Jan. 15, Agnant talked about her life’s story and writing to an audience of students, faculty, staff and community members in the West Gallery.

“The first years of my life in Montreal were some of the richest parts of my existence,” Agnant said. “It was a period of adaptation and personal growth in which I discovered how important it is to have the ability to be reborn. Being an immigrant, you die and come back to life in a way.”

After moving to Montreal, Agnant became embroiled in the city’s social justice movements. She credited these experiences, as well as her time in and departure from Haiti, as being what fuels her writing.

“My pain is a burning pain. It’s something that burns you up from the inside. When I’m writing, I’m sitting with a lot of luggage,” Agnant said. “And inside that luggage, there is the luggage from when my ancestors came from Africa and worked in the fields to build rich countries. I have luggage as a person whose ancestor fought slavery. I sit with my luggage from when my parents were paying the debt to France.”

Agnant spent some time discussing the concept of home and belonging after an audience member asked where she considers home to be.

“I stayed 20 years without setting foot in Haiti. For me, it was nonsense to leave a country where people cannot leave and are being killed, and to return as a tourist,” Agnant said. “At the end of everything, you find peace inside yourself. Traveling a lot made me become someone else. Today, I feel at home everywhere, but nowhere is my house. My house is inside me.”

Junior Chloe Wells was impacted by Agnant’s feelings regarding home.

“One of my major takeaways was (Agnant’s) reflections on home and what home feels like, and how she’s lived away from Haiti for so long while also trying to reconcile her relationship with it,” Wells said. “I really like the fact that her writing isn’t just about her. Her experiences can be so transitive for other people who have experienced being a refugee, and the experience of being misplaced. It’s her story, but it’s everyone else’s story too.”

Junior Jed Edwards was fascinated by the social justice and cultural aspects of Agnant’s work.

“I was previously unfamiliar with her work, but it was very inspiring to hear her motivations and how she takes these stories that have been forgotten and silenced and works to make them unsilenced,” Edwards said. “There’s a lot to be gained from how she represents the refugee and immigrant multicultural writer. She embodies this mixture of cultures that I find very enriching.”

In spite of the pain Agnant faces when thinking about and visiting Haiti, she upheld that her conviction to write and have hope was born out of necessity.

“There’s a difficulty to have hope, even when you try. You see even when there is destruction in a country, it is not just physical destruction, but also the people are destroyed, mind and soul,” Agnant said. “When I go back to Haiti, I cry a lot. I cannot suffer the indifference, but I understand the indifference is a way to stand the pain. Sometimes I say I’m tired, but you can’t stop. Once you see how the world is, you can’t stop.”