The struggle of constantly living on the brink

Addiction and substance abuse disorders bring suffering to a level of distress beyond the realm of what self-control and willpower alone can stymie.

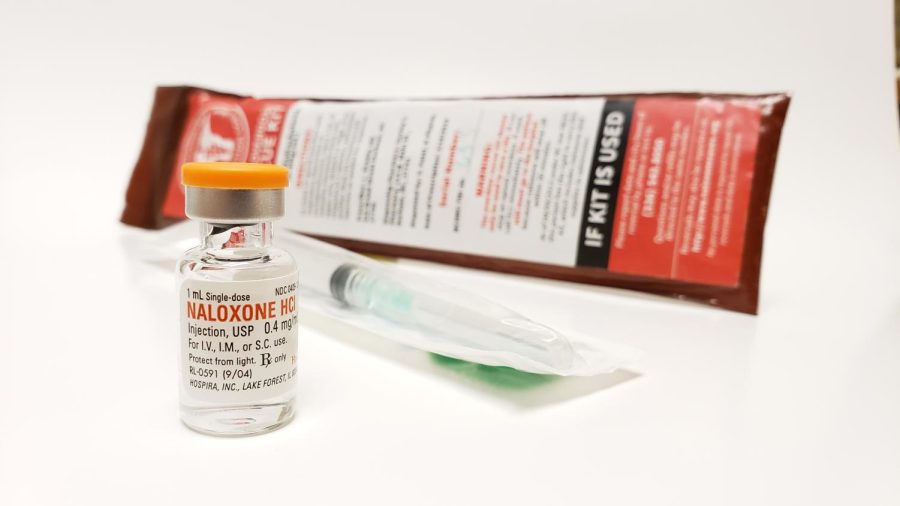

Mark Oniffrey via Wikimedia Commons

Overdose kits similar to this one can help save lives.

The addiction crisis impacts everyone from the famous and affluent to those on the least seen and most misunderstood margins of society, including undocumented immigrants, the chronically homeless and sufferers of sexual, physical and financial abuse.

The overdose crisis exerts a tremendous death toll. Knowing the exact amount of deaths is difficult, because overdose deaths often go unreported and death certificates take time to be included in the CDC count, but even the provisional count numbers are quite stark. In 2021, there were 4,041 overdose deaths in North Carolina, according to the state Department of Health and Human Services.

The common theme among all the testimonies I hear from harm reduction advocates, those in long-term recovery and those who have deceased loved ones is that those with substance abuse disorders are constantly living on the brink of disaster.

They are about to lose their job, their housing or both. They struggle with debt. They suffer from injuries, ailments and sicknesses beyond their control. They live at the whim of a landlord’s decision whether or not to evict, at the end of a family member’s patience, at the mercy of a stranger who helps them with small acts of kindness.

The obstacles to finding treatment are inhumane, controlling and disastrous. The prospects of having a child taken away if one seeks help from the government, finding oneself trapped between mandated rehab programs and prison with no way to pay for it or, in one case I heard about, having to go into more than $50,000 in debt to attend rehab are not unusual. The roadblocks faced by those in need of help are so daunting that I could not imagine having to make that decision for myself were I in the same position.

Mental health advocacy was never something I planned on pursuing, and I never fully grasped the terror of what it means to have thoughts that are out of control until I developed extremely disturbing obsessive-compulsive symptoms and became officially diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

Minor decisions to which I would previously never have given much thought began to grip my attention, driving me to reassess again and again to the point where I questioned my grip on sanity and free will. If I remember correctly, I have been to the emergency room about six or seven times, when my disorder caused total mental breakdowns. While finding treatment, I learned that the same neural mechanisms which cause obsessive-compulsive disorder are very likely to cause addiction, and that sufferers of OCD are more likely to become addicted to drugs to drown out the noise of their thoughts.

What hurt me most was that longtime friends and strangers alike simply could not comprehend who I was anymore. To the outsider, my moral character and inflictions seemed to be one and the same, and so I was judged as someone who had given up, was acting out and had little self-control. Meanwhile, I felt that the more I attempted self-control to push away thoughts, the stronger they became. I had the willpower and the support, but not the know-how.

There is no pause button to deal with the crises of life one at a time. In order to avoid losing a precarious spot on the brink, people who use drugs have to manage everything at once, especially their work and financial situations.

This is where harm reduction goes beyond traditional care. Done rightly, it is an approach that “meets people where they are, but does not leave them there,” as activists say. It is not only a treatment paradigm, but a social justice endeavor that rejects the penal approach to criminalizing addiction, and instead seeks to restore stability in life by giving people access to the housing, medical treatments, jobs, food and community they need.

I work with Guilford College alum Elizabeth Burke Beatty as a National Sea Change Coalition Fellow so that harm reduction, which is now contentiously debated for a variety of reasons, can be normalized and seen as the appropriate treatment response that it is.

There is much more I could say to argue in favor of harm reduction, but the only way I can start is by asking people to please listen from the heart when harm reduction is being advocated. Please, have sympathy for someone you have never met.

Their life may depend on it.

Elizabeth Burke Beaty • Mar 8, 2023 at 10:16 am

As an alum of Guilford and as the founder of SeaChangeRCO.org we are so honored to have you as our current Fellow! Thank you for all you do and what a great article. You are making a difference!