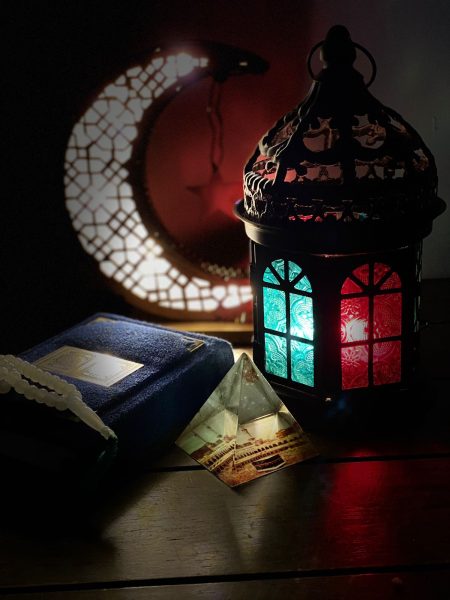

Violence causes refugee crisis

A burnt down house in a Rohingya village in northern Rakhine State, a result of sectarian violence in August 2017. Photo By Moe Zaw (VOA), via Wikimedia Commons

The story of violence against Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar’s northern region of Rakhine State is one that has lasted for decades. However, a new bout of violence erupted in the country on Aug. 25 when a militant group known as the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) attacked 30 police posts, resulting in the death of over 100 militants and civilians. In retaliation, the Myanmar army has killed Rohingya civilians.

According to U.N. Refugee Agency spokeswoman Vivian Tan, over 270,000 Rohingya Muslims have fled to Bangladesh over the past two weeks to escape from military retaliation that includes the burning of villages and the killing of men, women and children.

This violence against Rohingya Muslims and their subsequent displacement have yet to stop.

According to Wasif Qureshi, case manager for the human rights organization Islamic Relief USA, “Up to 15,000 people are expected to cross the Naf River into Bangladesh… each day this week.”

The current conflict and displacement of peoples in Myanmar is closely tied to the historical persecution of Muslims in Myanmar.

“There have been Buddhist instigators of deep violence and prejudice against the Rohingya for quite some time in northwestern Myanmar,” said Associate Professor of Religious Studies Eric Mortensen.

The Rakhine State has a poverty rate of 78 percent, as estimated by the World Bank, and has sharply divided religious lines. Approximately one-third of the country’s population of three million are Rohingya, and the other two million are Buddhist.

Myanmar’s government has historically sided with the Buddhist majority group, denying the Rohingya citizenship and the right to vote. Additionally, the government has placed restrictions on the Rohingya in terms of employment, education, religious choice, family size and freedom to move.

“This is really a historical problem,” said Zhihong Chen, associate professor of history. “(The Rohingya) were not given citizenship and (were) regarded as outsiders, so now they’re (being driven) away.”

The lack of citizenship for Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar stems from the idea that they are illegal immigrants from Bangladesh, despite the fact that many Rohingya can trace their lineage in the Rakhine state back for centuries.

“They never viewed (the Rohingya) as part of the people,” said George Guo, professor of political science at Guilford.

This attitude persists today, and prejudice against the Rohingya extends all the way to the Aung San Suu Kyi, the state counsellor of Myanmar. She has yet to recognize the exodus of Rohingya Muslims fleeing to Bangladesh or speak out against the violence.

“Aung San Suu Kyi has been and remains a beacon of freedom and hope for her people,” said Mortensen. “(That) is ironic given her confounding refusal to condemn, address, or act to stop the horrific violence to any effective or satisfactory degree.”

Many activists such as UN Secretary-General António Guterres and Nobel-Prize laureate Malala Yousafzai have implored Suu Kyi to take a stand against the violence in Myanmar.

“The authorities in Myanmar must take determined action to put an end to this vicious cycle of violence and to provide security and assistance to all those in need,” said Guterres to reporters.

This plea has yet to be answered. In addition, U.N. aid to Myanmar has been blocked throughout recent days.

“(Aid has been suspended) because the security situation and government field-visit restrictions rendered us unable to distribute assistance,” said the office of the U.N. resident coordinator in Myanmar, Renata Lok-Dessallien, to the Guardian.

Other organizations such as UNICEF, Human Rights Watch, Fortify Rights and Islamic Relief have stepped in to provide assistance to refugees.

“We are on the ground in Myanmar and in neighboring Bangladesh doing everything we can to get aid to people who are suffering,” said Qureshi. “(Our aid is) emergency food deliveries and other essential items that we can send readily.

“It’s been a challenge but we have been doing this for years now.”

Despite the influx of aid, the fate of the Rohingyan refugees is uncertain.

“Bangladesh might (do) … nothing because they don’t have (a) good economy; they are very poor,” said Guo.

Additionally, it is unclear whether or not the displaced Rohingya will remain in Bangladesh or migrate to other countries.

“Once they enter a region they … will stay … and call it home for the time being,” said Qureshi. “Depending on the politics in that region and how accepting they are, they might have another diaspora where they go to another country.”

With North Carolina ranking eighth out of all 50 states for resettling refugees, the Rohingyan crisis could have implications in the state. According to Qureshi, approximately 1,100 out of 3,711 refugees resettled in North Carolina in 2016 were from Myanmar.

With the relevance and local implications of the violence against the Rohingya in Myanmar, Guilford students need to be aware of what’s happening.

“I don’t think there is any limit to the growth of what is capable if people really want to aid the situation,” said Qureshi. “It just starts by building awareness and providing resources to the organizations that already have access.”