Indonesian fires rage on

While the sky above Indonesia fills with hazardous black smoke, the rest of the world has lowered its gaze.

Approximately 127,000 forest fires, spurred by illicit farming practices, have covered the country in a perilous cloud of environmental and public health problems.

For years, local impoverished farmers have regularly practiced illegal slash-and-burn techniques to clear forests and peat lands for growing palm oil. Now, larger palm oil plantations are cleaning immense expanses of land using the same techniques.

“A fire is going to be a very blunt instrument for converting natural ecosystems into man-made ecosystems,” said Kyle Dell, associate professor of political science and cochair of the environmental studies department. “For the most part, this will have a negative impact on the existing fauna in the area.”

The air has turned smoky yellow in the hardest hit areas, and currently more than half a million people have contracted some type of respiratory problem.

“These fires are releasing more carbon dioxide emissions each day than the entire United States,” said Interim Assistant Director of Study Abroad Robert Van Pelt ’15.

The Global Fire Emissions Database reported that the blaze has already generated 600 million tons of greenhouse gases, blanketing Southeast Asia in smoke visible from satellites.

Airplane travel has been heavily restricted, and schools have been closed in Indonesia, Singapore and Malaysia.

“If the forecasts for a longer dry season hold, this suggests 2015 will rank among the most severe (environmental) events on record,” said NASA scientist Robert Field to ABC Online Services.

Unlike typical accounts of large-scale fires, the inferno blazing in Indonesia has scorched the land as well as the trees. Because the country’s forests rest on peat land, soil made up of dense partly decomposed vegetable matter, the flames burn deep.

Smoldering soils smoke for weeks at a time, releasing more methane and carbon monoxide into the atmosphere.

“When you have a lot of peat, you get more haze and these absolutely extraordinarily levels of air pollution,” said Nigel Sizer, global director of the World Resources Institute to Time magazine.

So far, most of the country’s exotic and endangered species, such as orangutans, clouded leopards and sun bears, have been forced from their lands at an alarming rate.

Indonesia and Sumatra hold the remaining population of orangutans, and the blaze has placed a third of them in jeopardy.

“Those animals are unique to that region, and that’s what makes these fires are so disastrous,” said Van Pelt. “If all their land is being consumed, where exactly will they go?”

While recent rainfall has reduced the numbers of serious fires, world environmental agencies are calling on Indonesia to propose more effective measures to prevent future environmental crises.

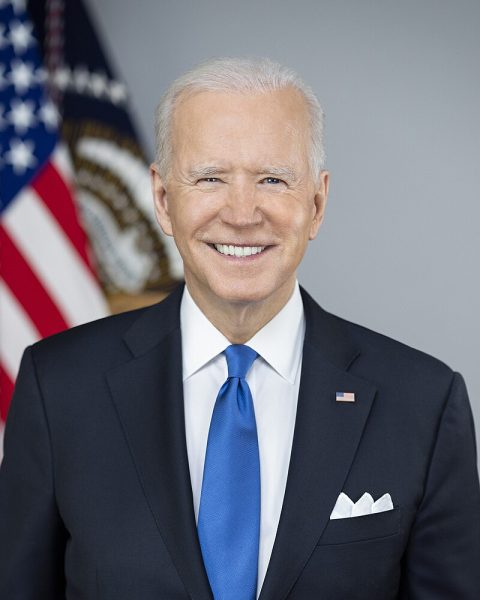

Indonesian President Joko Widodo has specifically proposed a system of requiring licenses to clear land.

“Unfortunately, the people who are setting these fires are doing so in order to feed their families today,” said Dell. “Simply telling them not to burn these forests the only way they can on this property does not help them survive.”

“These people are, economically, most vulnerable, and they are the ones who are living at the fringes of man-made society, closest to the most vulnerable ecosystems.”

Creating more viable options for impoverished peoples and confronting large corporations with unsustainable practices of farming may be the stepping-stones for widespread governmental change.

This fire season was worse than those in the past, but it was just part of a repeating cycle. If the cycle continues, there will be no space for orangutans and eventually no resources for the impoverished.

“Eventually when the fires die out, everyone moves on to other things, and people forget,” said Sizer. “Hopefully, this time it was so serious that that won’t happen.”

The Guilfordian • Nov 16, 2015 at 12:59 am

Hello, Richard. Thank you for bringing this to our attention! It has been corrected.

richard amstutz • Nov 15, 2015 at 11:37 am

Need to get Caleb’s last name spelled correctly. These great articles deserve author recognition! A Proud Father!!!