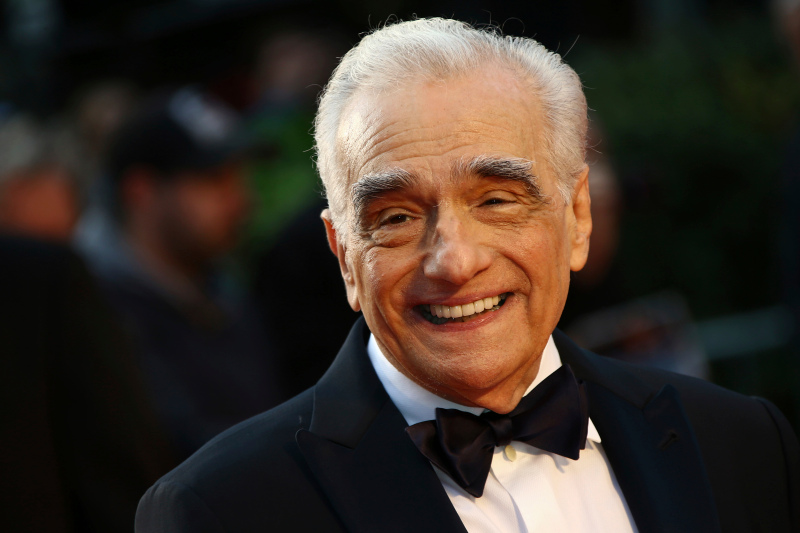

Martin Scorsese advocates film preservation

https://www.indiewire.com/2021/02/martin-scorsese-streaming-lack-of-curation-1234617241/

Towards the end of 2019, iconic film director Martin Scorsese came under fire on social media for his statements claiming that the Marvel Cinematic Universe wasn’t cinema and was more akin to theme parks. There was more to the quote for sure, and Scorsese even claimed that, although they weren’t for him, the films were often well-made. However, his comments still sparked a heated debate online regarding cinema and the MCU, drawing ire from comic book fans.

As such, all eyes were on Scorsese once again when news outlets published articles quoting from his essay “Il Maestro,” which was included in the March 2021 edition of Harper’s Magazine. One of the highlighted quotes from the essay read: “The art of cinema is being systematically devalued, sidelined, demeaned and reduced to its lowest common denominator.”

This quote lamented how film is commercially looked at as “content” rather than preserved as “art” by the industry.

Out of context, it’s easy to read it as Scorsese just flinging rotten tomatoes at comic book movies again like the old, jealous curmudgeon that comic book fans bitter towards his previous statements take him for. However, once you read beyond the headlines and cherry-picked quotes and delve into the articles or the essay peddled by sites such as IndieWire, it becomes clear that he takes issue with how film is presented algorithmically, and how film is preserved. It all revolves around a certain word: “content.”

In essence, the meaning of the word has shifted in usage; now it is used when discussing films in a commercial sense. Movies are seen more as marketable products by the film industry, and as pieces to be served via algorithms in streaming services such as Netflix and Hulu.

“If further viewing is ‘suggested’ by algorithms based on what you’ve already seen, and the suggestions are based only on subject matter or genre, then what does that do to the art of cinema?” Scorsese asked in the essay.

To be clear, there is nothing inherently wrong with streaming services providing films for audiences to enjoy. In fact, as Scorsese noted, “The best streaming platforms, such as the Criterion Channel and MUBI and traditional outlets such as TCM, are based on curating—they’re actually curated.”

His problem is with the industry and services treating the film viewer less as a fan of art, and more like a consumer of products. With an algorithm, films are displayed based on other movies you’ve seen on those streaming services, as well as what the services perceive your viewing habits to be. With curation, pieces of media are specifically picked to be preserved for those who wish to seek them out. The former hoards films to distribute and lose based on calculations and market demand, while the latter is more specialized and involved.

To better understand where Scorsese is coming from, one must look at the era in which he rose to prominence: the 1970s. Production codes had fizzled out, and a hip new system of age ratings such as G, PG and R was in. Films were allowed to tackle topics of violence, sex and LGBT+ issues more openly for the first time, and auteurs such as Scorsese reveled in crafting films that were edgier, heavier and more artistically driven.

This period came to be known as the “revisionist movement,” and lasted from the mid-1960s to mid-1970s. Film historians contest the validity of the movement, and those who accept it claim that it came to a close around the time when blockbusters such as “Jaws” and “Star Wars” broke mainstream box offices. However, the likes of Scorsese’s “Taxi Driver” still garnered success, and the director would make several critically acclaimed films such as “Goodfellas” and “The Wolf of Wall Street” for the next several decades. The current age of blockbusters, created by Disney and Warner Bros. several times a year for mass appeal, is radically different.

With the context behind the periods in which Martin Scorsese rose as a filmmaker, it’s easy to see why he considers film a cultural art form and a mode of expression rather than a corporate product. As such, it makes sense why he laments that film is seen as “business” first and “art” second. Curation is championed for this reason: it happens when cinephiles compile and share works they love with others in professional capacities like streaming services, and in more personal ways, like recommendations and lists on Letterboxd. Curation is more than just a film snob being picky about cinema and putting down more “lowbrow” and “mainstream” affairs. It’s an act of passion and preservation of art.

When Martin Scorsese pushes for the curation and preservation of films as an art form, he wants the medium to be experienced and appreciated, rather than locked away behind the likes of the infamous “Disney Vault.” As the founder of The Film Foundation, Scorsese understands that movies are not the same kind of content as the average commercial or YouTube video. They’re a medium of passion and expression, and are pillars of popular culture. As Scorsese himself put it: “They are among the greatest treasures of our culture, and they must be treated accordingly.”

On top of the films stored away until the next physical release decades later, there’s an indescribable number of silent era films from countries such as America and Germany alone that are now lost to time. You would not want your favorite films to suffer the same fate, would you?