Eccentric Expressionism: Weimar Republic cinema captures societal angst and upheaval

Expressionism was born in the chaos of a war-ravaged Germany in the beginning of the 20th century. A stark shift from traditional artistic mores that based art upon physical reality, Expressionism sought to capture a subjective emotional experience. Expressionist film exploded with popularity in the Weimar Republic, with the films’ subject matters echoing contemporary German society; social strife, the abandoning of traditions, and heavy, heavy angst.

Spearheaded by Professor of Foreign Languages Dave Limburg, Guilford will be host to a series of Weimar-era films, both Expressionist and otherwise, throughout the fall semester. 2019 is the 100th anniversary of two groundbreaking movies from the era: “Anders als die Andern” (or, “Different from the Others”) and “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.”

“Expressionism is freedom. You don’t have to stay within the boundaries of the frame,” Limburg said. “(Expressionists) take things that are supposed to look normal and skew them a bit, or make them jagged or make them distorted. That makes you think about things in a deeper way, I think.”

“Anders als die Andern,” which was shown on Oct. 9 in Duke’s Leak Room, is one of the first sympathetic portrayals of homosexuality in cinema, and perhaps the world’s first pro-gay film. Telling the tale of violinist Paul Körner, a gay violinst, “Anders als die Andern” protested Paragraph 175 in Germany’s criminal code that prohibited homosexual relationships between men. The film was eventually banned by the Nazis, with most copies being burned. The film may not be Expressionist, but it retains themes of social upheaval, ostracization and despair that are prolific throughout Weimar cinema.

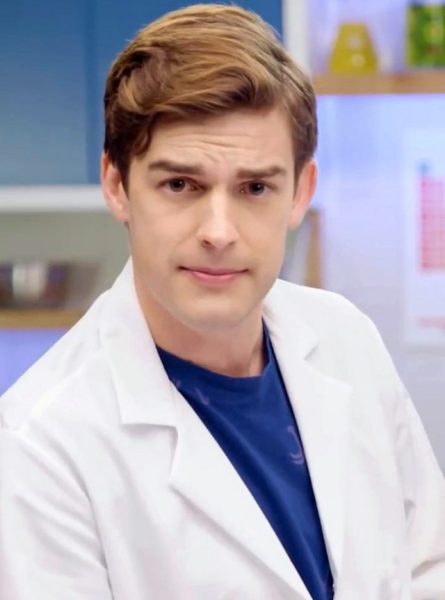

Senior Anthony Carr presented the film and lead the post-viewing discussion.

“For me, (“Anders als die Andern”) means change,” Carr said. “It signified the different thoughts in German society at that time. We think now these progressive ideas were so unreachable at that time, when in fact, they were really evident and present in the Weimar Republic.”

“The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” will be screened in Dana Auditorium in honor of its 100th anniversary and will feature a piano accompaniment by Professor Emeritus Tim Lindeman. The film was revolutionary; it is considered the quintessential Expressionist film, was called “the first true horror film” by movie critic Roger Ebert and is a forefather to arthouse and cult films.

“(Caligari) is known as the first big, super-successful art film, or ‘kunstfilm,’” Limburg said. “It’s a film that was trying to express something artistically, and not just telling a story or shocking people. It expresses ideas in a very creative way, and it might be the first German film that does that.”

The film features very bizarre and deliberate distortions of perspective and scale, featuring sets that seem to ominously fold into themselves, narrow, winding streets and staircases that ascend at sharp diagonals. Shadows are painted directly onto the set, lending it the appearance of a fever-dream drenched in subtle danger. A common thread of German art of the period was a sense of looming angst and horror.

“(Weimar films) would focus on monsters, creepy things or explosions. I think it comes from the angst of the time after getting through the world war, and all the problems of German society just seemed like chaos,” Limburg said. “And people were trying to deal with that.”

On Nov. 13, Fritz Lang’s drama-thriller “M” will be screened. Following a vein of unsettling topics, “M” is centered around the manhunt of a serial killer who targets children. The serial killer is portrayed by actor Peter Lorre, whose fish-eyed gaze and unnerving mannerisms create a sense of unease throughout the film.

“I think it’s interesting how they weave elements of reality and the prevalence of serial killers in the Weimar era. Fritz Lang’s commentary on social unrest and the criminals policing the killers is an incredible theme within the film and kind of before its time,” said senior Dylan Mask. “The film came out in 1931, and by 1933 the entire country was under an autocratic regime, the Nazis. It’s a really interesting film about the harsh realities of life in the late Weimar era.”

Editor’s note: This story originally was published in Volume 106, Issue 3 of The Guilfordian on Oct. 18, 2019.