Inputs and outputs: Haircuts and the Black experience

When I was growing my hair out, I was unable to go to the barbershop because of the pandemic. Growing out a smash player Afro with no lineup was not an option, but luckily, my father owned clippers.

Now that I’ve lined myself up twice, I’ve gained a new appreciation for the job he did. It was a smooth cut, and the lines on the side were sharp. The only issue was that, because he looked down on my shorter self while he cut my hair, I ended up with a high hair arc instead of a hairline.

As a result of my Stephen A. Smith cut, I didn’t let my father near my hair for a long time. I learned my lesson. This experience reinforced my preexisting beliefs about my hair.

The belief system I had was a good one. Whenever my barber cut my hair, it looked good, and my hair looked worse the longer I went without a haircut from my barber. This system explained why my hair would look good on some days and not others, and could provide guidance in times of stress. Whenever my hair got too messy, I let Rex, my barber, cut it.

All sound belief systems and good frameworks seek to do this. Their purpose is to explain some system of inputs and outputs and serve as a guide for future behavior. Sometimes, the system of inputs and outputs is simple, and the corresponding framework is as well.

The inputs (what happens to my hair) and the outputs (what my hair does)constitute a simple and easy-to-understand system. I wash it; it looks clean. I don’t; it looks dirty. I let Rex cut it; it looks good. I let my dad cut it; it looks good, maybe less so. Because this system is simple, the framework I use to understand my hair and what I should do with it is also simple, even if it is a bit more evolved today than just letting my barber cut it when it looks unkempt.

Simple frameworks are harder to form when the systems get more complex, and for black people, three things make it especially difficult to create a framework that explains our web of inputs and outputs.

For one, our experience as a people group is incredibly distinct. As a group made of many diverging ethnic and religious populations that have been disconnected from their home cultures, mashed together and pseudo-integrated into another dominant culture on a massive scale, our historical trajectory and conditions are unique in recent history. In explaining our reality, we can’t just borrow ideas from similarly situated cultures, because they don’t exist, and we can’t reach back into our cultural heritages, because we have no connection to them.

The second reason is that some of the things we experience are absurd and can be hard to explain. For example, many aspects of racial discrimination can feel bizarre and unreasonable. Continued economic despair juxtaposed with consistent efforts (well-meaning or not) from outside groups to help those struggling feels nonsensical. Our web of inputs and outputs has some weird outputs.

Third, the inputs are often unclear or unknown. The root causes of social ills and economic issues aren’t easy to understand in any society or culture without people being intensely devoted to their study, and there just aren’t that many folks studying black issues; African American studies isn’t the most popular of majors.

These factors combined mean that explaining the black web of experience is impossible. The web is too unique, the outputs often too confusing, and the inputs too understudied. The result is a people group who want a good framework but can’t find one, and either fill the void of reasons with whatever they can or get sucked into a negative feedback loop clinging to alternative, flawed frameworks.

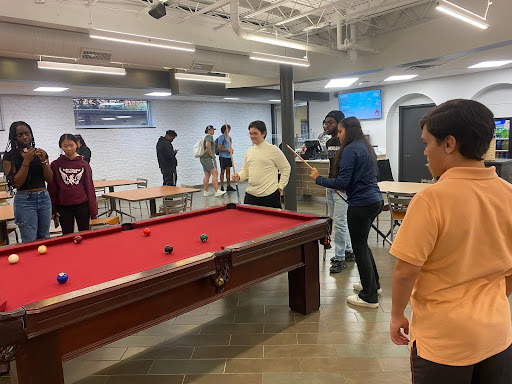

The solution here is to reduce the scale. A framework explaining why black America is the way that it is would be impossible to make, but one explaining the persistence of exacerbated black poverty or the more bizarre forms of racial discrimination is. We can’t explain every aspect of our existence in one go, but we could explain why our hair gets the response it does from non-black people, and we could explain why barbershops are often community centers.

If we keep going, we might not have one explanation for the black experience, but we will have a list that accomplishes the same goal: making sense of our, at times, nonsensical existence.