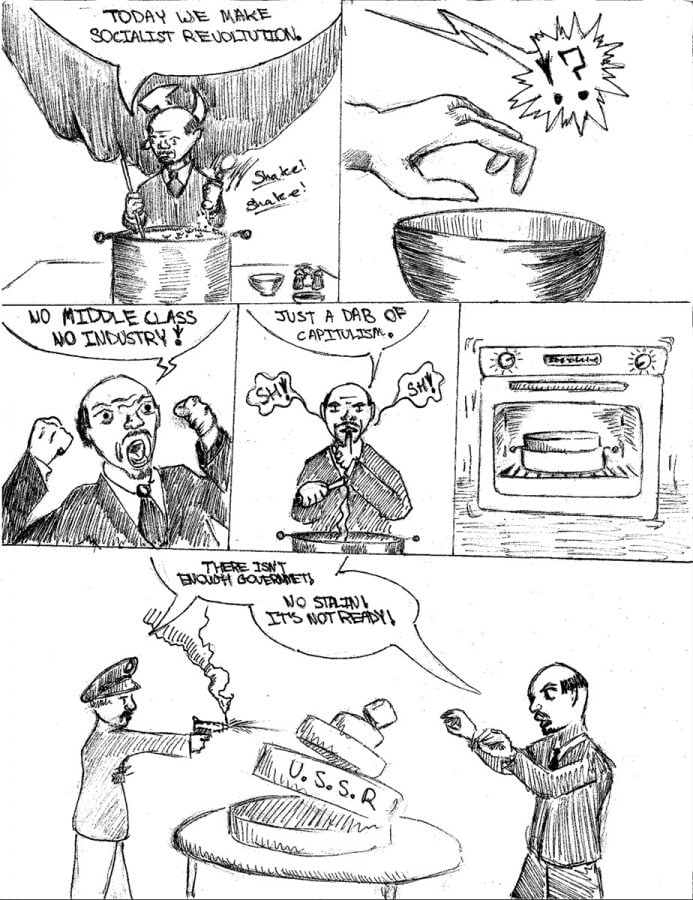

USSR’s capitalist experiment, effect

Marxist economic theory historical materialism rests on the premise that capitalism is an exploitative, even morally evil process which leads to inequality, social depravity, and the degradation of freedom. The Marxist objection to capitalism can be understood with the theory of surplus labor. In order for capitalists to make a profit, it is necessary to pay workers less than what they are worth.

“Marxism is the idea that working people can be supported by the state, that people can be marginalized by the market if the government doesn’t intervene,” said junior Mitzuo Kato.

This unequal transaction is the root of all the inequalities and injustices of capitalism, which the Russian Revolution, and civil war led by the Bolsheviks sought to abolish. This makes it supremely ironic then that shortly after the period of war communism, Lenin’s economic policy turned towards exactly that which the revolution fought to abolish, capitalism.

The reason for this actually has roots in Marxist thought. Marx theorized that a society would need to reach the capitalist stage of production before it could transition to socialism. Without first transitioning to capitalism, there would be no industry for the new revolutionary governments to direct, and thus, not much for the dictatorship of the proletarian to reappropriate. This is exactly the problem that revolutionary Russia ran into following the establishment of communism.

The first years of the new socialist republic saw a massive famine which the government could do little to alleviate. The system of wealth appropriation required peasants to pay most of their grain and produce to the state in order for it to be redistributed to all. The problem is that there were too many Russians and not enough food to be redistributed. Since peasants were not keeping the grain they produced, there was no incentive to increase their production when nobody else was willing to work.

“What happened was the state tried to seize all of the banks, they tried to get control over the commerce, they tried to get control over production, and it didn’t work,” said Voehringer Professor of Economics Robert Williams. “They had to out money to pay for all of it, and they had hyperinflation.”

At the Tenth party Congress, Lenin convinced the soviet leaders to adopt a New Economic policy of limited capitalism still girded by the state. Under this system, the government allowed private ownership of land and business, but the so called “commanding heights” of the economy, heavy industry, foreign trade and finance were still left in the hands of the state. The goal was not to permanently switch to capitalism, but to provide a temporary stepping stone towards full communist control of the economy.

“The civil war devastated the economy, and many of the owners of the economy fled to Europe,” said Associate Professor of Economics Natalya Shelkova. “The revolution was not intended to allow private property, but the new economic policy did for small scale entrepreneurs.”

The Tsarist regime left Russia fairly destitute and deindustrialized. Allowing some capitalism would increase the levels of industrialization, building an urban proletariat, the class which Marx envisioned would be best suited to carry out a dictatorship of the proletariat. Lenin reintroduced the monetary system and allowed peasants to sell some of their surplus grain, giving them an increased incentive to work. Even foreign enterprises were allowed to operate in Russia. This was a radically pragmatic move for such an idealist revolution, but Lenin embraced it

“You will have capitalists beside you, including foreign capitalists, concessionaires and leaseholders. They will squeeze profits out of you amounting to hundreds percent. They will enrich themselves, operating alongside of you,” Lenin said. “Let them. Meanwhile you will learn from them the business of running the economy, and only when you do that will you be able to build up a communist republic.”

He rationalized taking help from the West with a faith that Russia would eventually surpass the west. The New Economic Policy was successful, but only lasted temporarily. Production tripled, surpassing pre-war tsar era levels.

“They allowed small producers and peasants to sell their products, so the New Economic Policy was very effective in increasing production and reducing inflation,” Williams said.

The private independent trader, the NEP man, actually became the new symbol for the era, perhaps surpassing the importance of the revolutionary oil field worker Ivan.

“It produced a lot of short term positive results, but only in specific areas,” Shelkova said. “You couldn’t own a large factory, you could probably own a shop.”

However, the death of Lenin, the NEP’s mastermind, coincided with Soviet leader’s abandonment of the NEP. The country’s next economic policy, the Five Year Plan, would take a much less liberal approach to development. Under Stalin’s Five Year Plan, the government would create, own and orchestrate the development of a fully fledged industrial syndicate and the collectivization of agriculture.

“Stalin closed off that window of opportunity basically,” Shelkova said “ He started the Stalin era industrialization, which was large scale. A lot of sweat and hard labor, much of it forced labor.”

Adopted in 1928, the Five Year plan called for a 250 percent increase in industrial production in just five years. Many new industrial centers were developed, especially in the Ural Mountains, and peasants were forced onto collective farms. These collective farms were large-scale government owned operations designed to increase agricultural production to finance and feed Russia’s ambitious industrialization.

The newly industrialized state would be a priceless, classless, command economy to serve as a model for other communist revolutions to show that socialism could compete with western capitalism.

The reality of the five year plan was brutal misery. Almost all of the private property and tradesmen of the NEP era was done away with. Unwilling to cede so much of their individual liberty, peasants fiercely resisted collectivization. Stalin blamed famines on the Kulaks, well to do peasants, for withholding grain, and he retaliated harshly, enacting the deportation of five million members of that class.

Afraid of what would happen if they were found to fall short of quotas, local authorities of collectives sometimes simply made up numbers. The collectivization did not significantly increase productivity, for although Stalin collectivized 97 percent of the peasant population, the collectives lacked the machines that would increase productivity.

Walter • Feb 1, 2019 at 6:18 am

Communism has led to millions of deaths every single time it’s been tried. It destroys economies every single time it’s been tried (see: Venezuela). It sickens me that many of my peers see capitalism as the worse system. Have we learned nothing? Even in this article, the horrors of communism have been whitewashed away. I’d encourage anyone interested to read The Gulag Archipelago. Those who have little knowledge of history may be destined to repeat it.