US impacts future of global free trade

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Adam Smith and David Ricardo, two founding fathers of economics, put forth theories that laid the groundwork for modern free trade. Today, the future of the global trade economy may be up in the air.

“Pretty much a big word right now is ‘uncertainty’ depending on what kind of trade deals are going to happen or tariffs, that kind of thing,” said Austin Seibert, a senior economics and sports management double major.

This uncertainty largely originates from the United States.

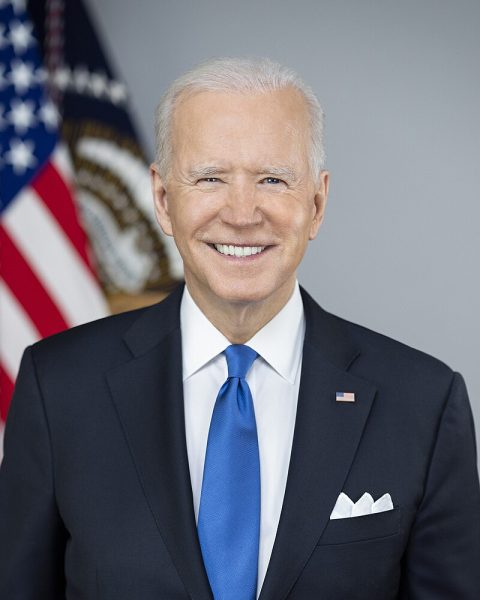

On the 2016 presidential campaign trail, trade policy was front and center. Many candidates shied away from policy positions embracing free trade, but Republican Party nominee Donald Trump railed against them.

“Our politicians have aggressively pursued a policy of globalization, moving our jobs, our wealth and our factories to Mexico and overseas,” said Trump during a June 28 speech in Monessen, Pennsylvania.

On Jan. 23, three days after his inauguration, President Trump signed an official memorandum withdrawing the U.S. from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a 12-nation trade agreement.

Without American participation, TPP is virtually dead. Prospects for another proposed accord, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, are in doubt, as is the future of NAFTA.

“I think it’s kind of like a natural response to globalism from the far-right, and it’s kind of come full circle now,” said Jonny Goffredi, a senior majoring in economics and history.

Paradoxically, U.S. public support for free trade has been generally high.

According to a Gallup survey conducted in February of 2016, 58 percent of Americans thought foreign trade presented an opportunity, not a threat, to the U.S. economy. A similar Pew Research Center poll from March of 2016 found 51 percent of American thought free trade agreements were a good thing.

But in those surveys, conservative respondents thought more negatively about foreign trade. Two-thirds of Trump supporters thought free trade agreements were a bad thing.

Orthodox theories on trade are clear.

“Free trade allows countries to get what they need and also sell what they have,” said Seibert. “Likewise, it allows certain countries to be the gold standard in certain things.”

International trade also tends to benefit some groups more than others.

Businesses in developed nations lose out to cheap foreign competition. Developing nations are bottlenecked into specializing in less profitable industries, creating unequal exchanges.

But shoppers stand to gain.

“Does the consumer win because we have Walmarts everywhere and we can buy everything cheaper?” said Goffredi. “In one sphere, the consumer does have a wide range of products from all over the world that we can buy, and that’s the beautiful part of globalism.”

Another wrinkle in trade is the impact of technology.

“Trump blames NAFTA for our jobs leaving, but I think it’s more so technological innovation,” said Goffredi. “If you look at output in production, we’re not producing less because we’ve given all our jobs elsewhere. A lot of those manual labor jobs or lower-skilled jobs are just automated now.”

The current economic climate has led some nations to reconsider their priorities.

“I think it’s also important to talk about how the United States isn’t alone in this step back from globalism, especially the prime example being Great Britain and Brexit,” said Goffredi. “That’s another bombshell in trade where you see countries that once were the pioneers in opening up the world for free trade and exploiting labor and natural resources abroad are now walking that back because … the principles behind free trade don’t change.”

In British and U.S. history, tariffs and barriers to trade helped build and protect industries. As national economies grew, so did the desire to sell goods abroad. The duties on imported goods, however, meant equally high tariffs on exports.

Following World War II, the emerging superpower U.S. led efforts to craft a framework for barrier-free world trade, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. GATT later became the World Trade Organization, which has 164 member states today.

With the U.S. taking a step back, other trade blocs could take the reins.

“Most economies look to the U.S., having the world’s largest economy, and then China, second largest economy in the world,” said Seibert. “Pretty much everything goes off what happens in these two countries.”

China and the 28-state European Union are formidable economic powerhouses in their own right. One or both could supplant the U.S. in the years to come.

This has some considering the political implications.

“Trade has always also been linked to geopolitical strategy,” said Goffredi. “What I mean by that is, the TPP, what that would have done in Asia is put a significant United States presence in the region that would put pressure on China.”

Critics lambasted trade deals like TPP and TTIP, though. Experts and activists disliked the supposed corporate influence on the agreements as well as their potential impact on intellectual property rights, free information and the environment.

Still, the future of global trade rests in the hands of big players.

“The big movers in each kind of market — whether it’s stocks, commodities, bonds — the big movers are going to dictate what goes around,” said Seibert.