South African students protest rising tuition, inequality

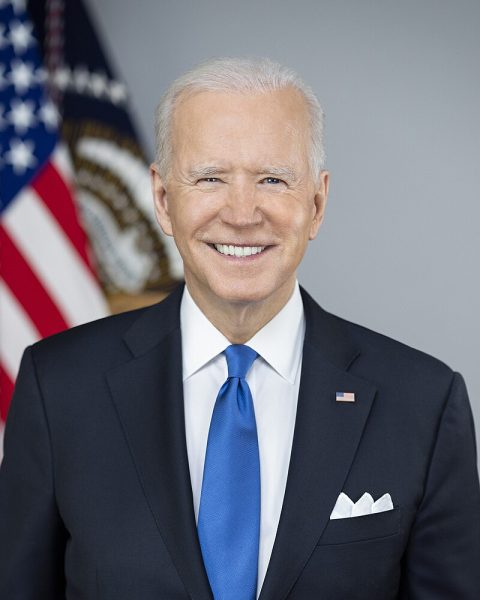

Courtesy of Masixole Feni/Groundup.org

Police watch a student protest on Oct. 22, 2015. The students managed to convince President Jacob Zuma to suspend tuition increases for a year.

On Oct. 23, the largest student protest since 1974 occurred in South Africa.

In the nation’s capital, Pretoria, thousands of college students objected to an 11.5 percent tuition hike proposed by universities to cover their operating expenses.

For many, however, the rally was not simply about the price of education. Following the end of apartheid in 1994, countless socioeconomic issues persisted, many of which have been contributing to rising tensions.

The average white South African household still makes six times as much income as the average black household. In addition, only 35 percent of black students graduate high school, compared to 76 percent of their white peers.

Furthermore, South Africa has the highest level of income inequality of any nation, with the top 20 percent earning almost 80 percent of the income.

“Because (South Africa) is so racialized, having really expensive college means that higher education is going to be very imbalanced in terms of its ethnic makeup,” said South African Early College junior Danielle du Preez.

“White people will have access to college education while black people, the majority of the population, will not.”

In a televised broadcast, South African President Jacob Zuma agreed to the demonstrators’ requests, halting the proposed increase, but only for 2016.

“It’s always that kind of political game, kicking the can down the street,” said Interim Director of the Study Abroad Daniel Diaz. “I think it will come to a head again.

“Unless the students are able to organize and work towards the goal of transparency, you will see these protests coming back.”

South Africa is not the only country with economic problems related to its higher education. The U.S. student loan debt, for example, exceeds $1.2 trillion. At an average U.S. salary, it would take a person close to 500,000 lifetimes to earn this much money.

“In the United States, we expect tuition to go up,” said Diaz. “We are almost at the point where no one is saying anything about it because it’s just the way it is.

“It’s unfortunate that we are so complacent, as compared to the students in South Africa, who are saying, ‘No, we don’t want that, that’s not how we should be treating education.’”

Some Guilford students believe that the price of college is high and the return is low.

“The (tuition prices) are outrageous,” said first-year Fawad Walizai. “Right now, there are many undergraduate students with enormous student loans who can’t find a job.”

Although many people acknowledge the extent of the crisis, it is difficult to come up with solutions for South Africa. One proposal is for the administration to work its way up through the school system.

“It will help for the government to start reforming education from a lower level,” said Preez. “This will give people who are impoverished or unemployed a better chance at being successful.

“In the U.S., for example, we need general education reform but most of our remedies are targeted at higher education, which are ineffective.”

The fate of education in South Africa is unclear. It could be that this protest is a catalyst for major socioeconomic restructuring. The protest may also be a lone event with no significance in the future.

Either way, education reform will be a vital step in remedying South Africa’s inequality.

“Education empowers people to learn to be appreciative of diversity and of others,” said Professor of Education Studies David Hildreth. “It allows folks not to be so zeroed in on their own affairs, to be critical and to question.”