Every campus a refuge: embodying our values

The refugee crisis is a perpetual crisis. As long as there has been conflict, there have been refugees. I myself am the child of refugees, their first, born in a country right across the river from the one they fled. We were lucky; my family escaped the drudgeries of the refugee camps to live a life of tenuous citizenry in the “alternate homeland.”

Others around the world are not so lucky. Many are settled where they initially arrive, their tents simply morphing into the sturdier, stiflingly close, zinc-roofed rooms of the shantytowns. Still many others never complete the perilous journey; countless migrants and refugees have drowned at sea in capsized boats and rafts, asphyxiated in the cargo holds of otherwise seaworthy and roadworthy vessels, succumbed to the limitations of their bodies, the elements, and the relentless indifference, if not cruelty, of the watching and waiting human race.

And then there was Aylan Kurdi. His little body, so seriously dressed for a dark and serious passage, moored by death on the shores of a resort town in Turkey, broke our hearts. Europe’s conscience quickened, for a short time. Hungary eased its chokehold on thousands of refugees trying to make their way north. Germany briefly accepted with open arms the streaming multitudes. And the Pope called on every parish in Europe to host one refugee family.

But what do academic institutions do with broken hearts? With the dead and dying bodies? With the endless convoy of humanity trying to make its way from misery to the unknown? What is our responsibility as teachers, students, and administrators of higher learning?

Our go-to is to educate, raise-consciousness, lift awareness. These are more than admirable goals. What is nobler than the desire to impart knowledge, broaden horizons, and engender meaningful, productive and useful conversation?

Fundamentally, however, these are endeavors firmly ensconced in the life of the mind, predicated on the belief that the mind will influence the soul which will influence the body which will then do.

But what if we saw the university or college campus not as a disembodied beehive of thinkers and learners but as a place, as much a body as it is a mind?

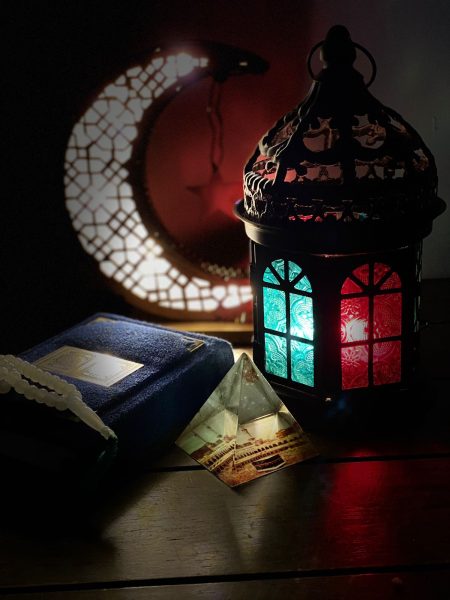

Indeed, a campus is a body: it is a body politic — a self-sufficient, self-governing, self-regulating city. The word for a university or college “campus” in Arabic is haram; it means a physical space that is both “sacred” and “inviolable” — a sanctuary, a refuge.

If we saw the college and university campus in this other embodied way, could we not then expand our response to the refugee crisis? If the EU and the UN have called on European and Arab nations to take in their “quota” of refugees, and if the Pope called on every parish to take in a refugee family, could we not then see the college or university campus as similarly responsible as a “country” or as a “parish”? We have the means — housing, cafeterias, a clinic, and people with various skills, resources and expertise — to host one refugee family on our campus and to assist them in successful resettlement in Greensboro.

Such an act would simply be a lived manifestation of Guilford’s core values and Quaker testimonies, an embodied expression of principled problem solving and our mission to engage “all things civil and useful,” and an extension of our campus’s historical legacy as part of the Underground Railroad.

In the face of the humanitarian disaster at hand, the cost of hosting one refugee family on campus grounds is truly minimal, the rewards astronomical. Concentrated pressure on particular areas and regions would be eased, quotas would be meaningless, and refugees would find a small country whose citizens share the burden, responsibility and joy of giving them a campus — a refuge.

A longer version of this article previously ran in the online magazine Jadaliyya.